Have Australian foreign interference laws made Communist Party China linked payments money laundering offences

by Ganesh Sahathevan

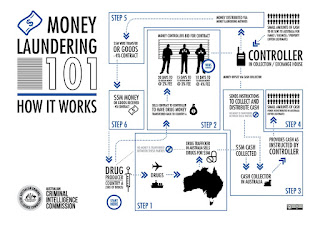

Money laundering | Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission

While donations to Australian political parties from foreign sources have been banned recently there remains the issue of Australian political parties, politicians and their backers being funded by foreign governments and their agencies using the same methods and structures used to launder money.

Such donations may still be received without penalty provided the structures are sufficiently layered so as to ensure that the identity of the ultimate donor is concealed.

Expecting local politicians to be provide full and complete details of the ultimate donor is not realistic, and frankly quite naive.

However the recent enactment of foreign interference laws might have changed matters such that recipients of political donations may have no choice but to disclose the identity of the ultimate donor, and in fact make every effort to determine the identity of the donor where it is not known.

While the foreign interference laws concern espionage and foreign influence and interference it is not difficult to see how an investigation into any of these is more than likely to involve an investigation of a money trail.

Where an investigation pursuant to the foreign interference laws involves a politician, political party or other political entity involves a money trail, it is not inconceivable that the investigation would involve the following elements:

a) a foreign slush fund

b) a source of financing for that fund that is illegal, as was the case in the Malaysian 1MDB scandal, misappropriated from a taxpayer funded source.

c) payments from the slush fund to some Australian politician or political entity

It is hard to see how, when the above or similar circumstances arise, the donees would not be in breach of Australia's anti-money laundering rules.

Even where the funds are from a legitimate source, say a Chinese company's Australian subsidiaries CSR or advertising fund, an offence may well arise in the case where the Chinese company is known to be linked to some Chinese government propaganda, foreign influence or espionage agency.

A contribution by such a company could come within the provisions of the foreign interference law, and the funds could then be deemed to illicit; regardless of interpretation of the relevant legislation it is hard to see how funds identified by say an intelligence agency as having some foreign source and intended to say influence the outcome of an election might be perceived otherwise. Public perception cannot be ignored. for political parties are ultimately judged not by courts but by voters.

However, without any conviction in a court of law such funds can still find their way into the political system as a donation to a seemingly reputable Australian political entity, and cleansed.

The persons then responsible would be the recipients, the reputable Australian political entities, and hence the argument for the recipients to be charged pursuant to the provisions of Australia's money laundering laws (as applied in the context of the the foreign interference laws).

The above should be read in the context of the debate about the distinction between intelligence and evidence. While intelligence may not be admissible as evidence, ignoring intelligence can, as shown above undermine the the integrity of our system of governance, including the justice system.

END

See Also

A criminal asked to design Australia’s anti-money laundering laws would probably keep the ones we’ve got

Summary of existing money laundering laws from the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions

Money laundering | Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission

While donations to Australian political parties from foreign sources have been banned recently there remains the issue of Australian political parties, politicians and their backers being funded by foreign governments and their agencies using the same methods and structures used to launder money.

Such donations may still be received without penalty provided the structures are sufficiently layered so as to ensure that the identity of the ultimate donor is concealed.

Expecting local politicians to be provide full and complete details of the ultimate donor is not realistic, and frankly quite naive.

However the recent enactment of foreign interference laws might have changed matters such that recipients of political donations may have no choice but to disclose the identity of the ultimate donor, and in fact make every effort to determine the identity of the donor where it is not known.

While the foreign interference laws concern espionage and foreign influence and interference it is not difficult to see how an investigation into any of these is more than likely to involve an investigation of a money trail.

Where an investigation pursuant to the foreign interference laws involves a politician, political party or other political entity involves a money trail, it is not inconceivable that the investigation would involve the following elements:

a) a foreign slush fund

b) a source of financing for that fund that is illegal, as was the case in the Malaysian 1MDB scandal, misappropriated from a taxpayer funded source.

c) payments from the slush fund to some Australian politician or political entity

It is hard to see how, when the above or similar circumstances arise, the donees would not be in breach of Australia's anti-money laundering rules.

Even where the funds are from a legitimate source, say a Chinese company's Australian subsidiaries CSR or advertising fund, an offence may well arise in the case where the Chinese company is known to be linked to some Chinese government propaganda, foreign influence or espionage agency.

A contribution by such a company could come within the provisions of the foreign interference law, and the funds could then be deemed to illicit; regardless of interpretation of the relevant legislation it is hard to see how funds identified by say an intelligence agency as having some foreign source and intended to say influence the outcome of an election might be perceived otherwise. Public perception cannot be ignored. for political parties are ultimately judged not by courts but by voters.

However, without any conviction in a court of law such funds can still find their way into the political system as a donation to a seemingly reputable Australian political entity, and cleansed.

The persons then responsible would be the recipients, the reputable Australian political entities, and hence the argument for the recipients to be charged pursuant to the provisions of Australia's money laundering laws (as applied in the context of the the foreign interference laws).

The above should be read in the context of the debate about the distinction between intelligence and evidence. While intelligence may not be admissible as evidence, ignoring intelligence can, as shown above undermine the the integrity of our system of governance, including the justice system.

END

See Also

A criminal asked to design Australia’s anti-money laundering laws would probably keep the ones we’ve got

Summary of existing money laundering laws from the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions

Money laundering involves hiding, disguising or legitimising the true origin and ownership of money used in or derived from committing crimes. It is an extremely diverse activity that is carried out at various levels of sophistication and plays an important role in organised crime.

There is no single method of laundering money.

Money laundering methods

Money launderers often use the banking system and money transfer services. However they are imaginative and are constantly creating new schemes to circumvent the counter measures designed to detect them.

Money laundering schemes may include moving money to create complex money trails, making it difficult to identify the original source and breaking up large amounts of cash and depositing the smaller sums in different bank accounts in an effort to place money in the financial system without arousing suspicion.

Prosecuting money laundering offences

Money laundering prosecutions are complex as they often involve complicated factual circumstances and dealings carried out in foreign jurisdictions. This means may mean we need overseas cooperation and evidence to assist in our investigation and prosecution of the matter.

Prosecuting these offences often requires detailed financial analysis and evidence.

We are continuing to deal with an increasing number of prosecutions of money laundering matters as law enforcement agencies ‘follow the money’ in the investigation of serious and organised criminal activity.

Key legislation

Main offences

Money laundering offences are set out in Part 10.2 of the Criminal Code and encompass a wide range of criminal activity.

- Sections 400.3 to 400.8 of Criminal Code: Dealing with money or property that is the proceeds of crime or intended to become an instrument of crime;

- Section of the 400.9 Criminal Code: Dealing with property reasonably suspected of being proceeds of crime.

Section 400.3 to 400.8 of the Criminal Code make it an offence to deal with money or property that is the proceeds of crime, or intended to become an instrument of crime. The offences in section 400.3 to 400.8 are all similar, however each section relates to money or property of a different value. For example, the offences in section 400.3 apply where the money or property dealt with was worth $1 million dollars or more.

- Sections 400.3 to 400.8 each contain three different offences with a maximum penalty that is tied to the state of mind (fault element) of the defendant when dealing with the money or property. Whether the offence is classified as being contrary to subsection (1), (2) or (3) depends on the state of mind the defendant had (belief/intention, recklessness or negligence) about the nature of the money or property. A table setting out the maximum penalties for each of the offences in Sections 400.3 to 400.8 is below.

Section 400.9 of the Criminal Code contains a different type of money laundering offence. This offence applies to dealings with money or property which is reasonably suspected to be the proceeds of crime and does not require proof that the defendant has a particular state of mind about the nature of the money or property.

Offences contained in the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act 2006 are also often used in prosecuting money laundering, in particular the following sections:

- Sections 142–143 — structuring offences

- Sections 53, 55 — the movement of physical currency both in and out of Australia

- Sections 136–138 — opening of bank accounts using false customer identification documents

- Sections 139–141 — use of bank accounts in false names or failing to disclose the use of 2 or more names.

Penalties

Sections 400.3 to 400.8 of the Criminal Code

| 400.3 | 400.4 | 400.5 | 400.6 | 400.7 | 400.8 | ||

| Value of money/ property | $1 million or more | $100,000 or more | $50,000 or more | $10,000 or more | $1000 or more | Any value | |

| Penalty | ss (1) Belief/Intention | 25 years | 20 years | 15 years | 10 years | 5 years | 12 months |

| ss (2) Recklessness | 12 years | 10 years | 7 years | 5 years | 2 years | 6 months | |

| ss(3) Negligence | 5 years | 4 years | 3 years | 2 years | 12 months |

10 p/units

|

Section 400.9 of the Criminal Code

The maximum penalty for an offence contrary to section 400.9 is 3 years’ imprisonment if the property is valued at $100,000 or more, or 2 years’ imprisonment if the property is valued at less than $100,000.

Partner agencies

- Australian Federal Police

- Australian Border Force

- Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre

Comments

Post a Comment